Bell's experiment

Why Bell inequalities exclude hidden variables?

Before all: it only excludes \textbf{local} hidden variables.

Einstein, Podolsky, Rosen and Bohm thought a gendaken that consisted of two particles, positron and electron, carrying opposite spins and emerging from the same neutral $\pi$ meson. They claimed that if QM is true (the spin is under superposition until we measure it), then the measurement of, say, the electron would imply an instantaneous action over the positron, which could be far away from the electron. And this is in contradiction with relativity. So there must be hidden variables in the system that determine the spin of the electron and positron before they emerge from the pi meson.

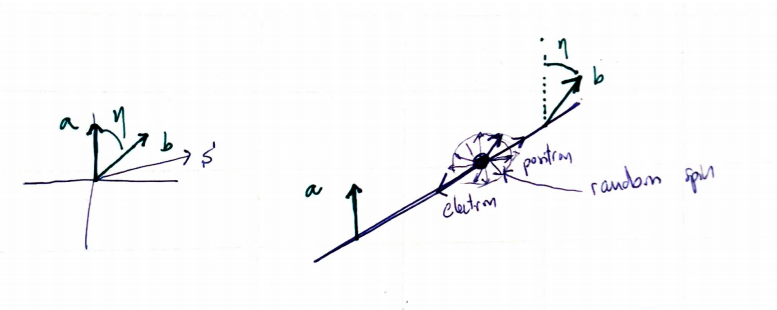

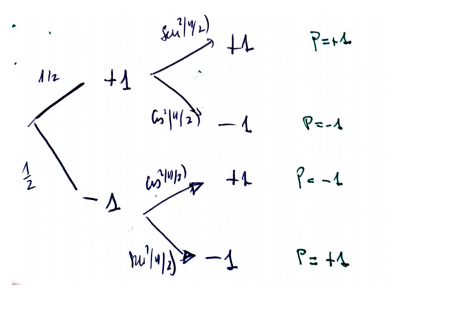

But Bell modified the experiment in the following sense. He thought about measuring both spins (electron and positron) at different angles, turning slightly the detectors. Assigned a value to the detector result: +1 and -1, and kept track of the product of the results of both detectors to compute their average: $P$.

Subquestion: why the product? Because this way is easy to follow the correlation. The product being -1 is what it should be if we had perfectly aligned detectors. I we turn a detector a little we would sometimes get a +1]

Now, think in a classical context: the electron and positron are balls with opposite spin (=angular momentum), but with random orientation, and our detectors only give us the sign of the projection of the spin over the orientation vector of the detectors (call them $a$ and $b$).

By simple probabilities calculations (total probability theorem) we obtain that $P=\frac{2|\eta|-\pi}{\pi}$.

But according to QM the balls would be in an entangled state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{a_+}\ket{a_-}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{a_-}\ket{a_+}$ (in the base given by eigenstates of detector $a$).

If we measure the electron and obtain +1 the state collapse to $\ket{a_+}\ket{a_-}$ so the positron is in state $\ket{a_-}$. If we express it in the other basis

$$ \ket{a_-}=\alpha\ket{b_+}+\beta\ket{b_-}=sin(\frac{\eta}{2})\ket{b_+}+cos(\frac{\eta}{2})\ket{b_-} $$I conclude that because $\alpha^2+\beta^2=1$ and because $\beta^2-\alpha^2=cos(\eta)$ since the average measurement of $\ket{a_-}$ in detector $b$ should lead to a classical result $cos(\eta)$.

Analogously

$$ \ket{a_+}=cos(\frac{\eta}{2})\ket{b_+}+sin(\frac{\eta}{2})\ket{b_-} $$So, using total probability theorem

So CM and QM disagrees. Experiments, of course, give the reason to QM. Observe that the \textbf{hidden variable $\eta$} is not enough to explain reality.

But what about any other alternative theory to CM with more hidden variables or with other probability distribution of the variable (above we have supposed that the random angle $\eta$ is uniformly distributed)?

Let's see. Supposse that the pairs electron-positron comes with a set o hidden variables $\lambda$ with a probability distribution $\rho(\lambda)$. Call $A(a,\lambda)=\pm 1$ the result given by detector $a$ for the electron with variables $\lambda$. And the same for $B(b,\lambda)$ and the positron in $b$ detector. Of course $B(b,\lambda)=-A(b,\lambda)$. Then

$$ P(\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b})=-\int \rho(\lambda) A(\mathbf{a}, \lambda) A(\mathbf{b}, \lambda) d \lambda $$I we now consider another detector.. (This is in chapter Afterwords, in Griffiths)...

Related: On Many Worlds, entanglement and hidden variables.

________________________________________

________________________________________

________________________________________

Author of the notes: Antonio J. Pan-Collantes

INDEX: